Strategy

Finding the product in your platform

On the risks of over-emphasizing platform thinking

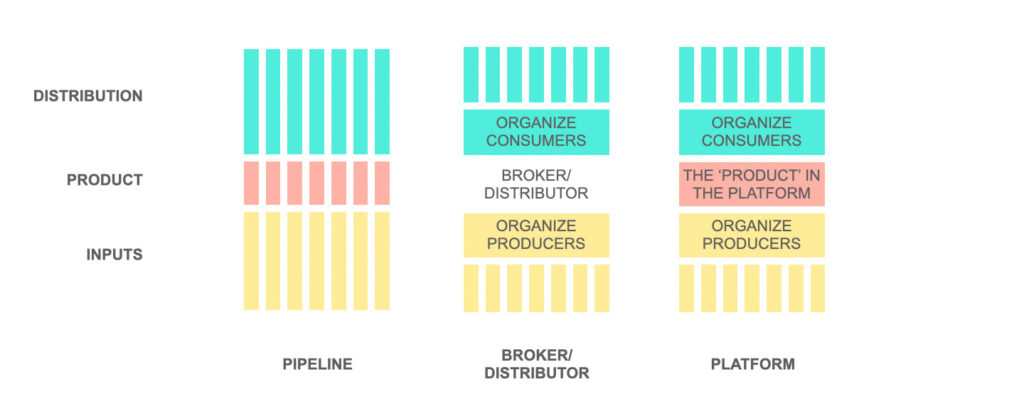

Playlists are the core product driving discovery of new artists. They are critical for Spotify to gain a right to sit in the middle of the music value chain and not be merely a digital distributor for the top 3 music labels.

Feel Free to Share

Download

Our Insights Pack!

- Get more insights into how companies apply platform strategies

- Get early access to implementation criteria

- Get the latest on macro trends and practical frameworks

The product in Kindle’s platform

What’s the ‘product’ in Kindle’s platform?

Again, books are inputs into the self-publishing value chain, so what is the ‘product’ that Amazon creates?

You’d be tempted to say that the physical reading device – the Kindle – is the product. That’s partly correct. The Kindle reader did introduce innovations like the e-ink electronic paper, which transform the reading experience.

But the Kindle is primarily a proprietary distribution channel, performing the same role that Spotify’s streaming technologies play. That is why it is subsidized and sold at a really low price.

So what exactly is the ‘product’ that Amazon is creating between the inputs of books and the proprietary distribution of Kindle.

Amazon’s ‘product’ is the community of book reviewers that Amazon has built up over time.

Hang in there while I unpack this: we’re not saying that the reputation system itself (as was the case with Airbnb) is Amazon’s ‘product’.

No!

To be very precise, Amazon’s production in the ebook value chain – its unique value-adding contribution beyond shaving off distribution costs – is the creative capacity of its community book reviewers.

Book reviews are critical to discovery of new books, particularly by first-time authors. But creating a robust book review and rating system is non-trivial. Unlike most product reviews, useful book reviews require significant investment of time and effort on the part of the reviewer. Hence, curating a community of book reviewers is non-trivial.

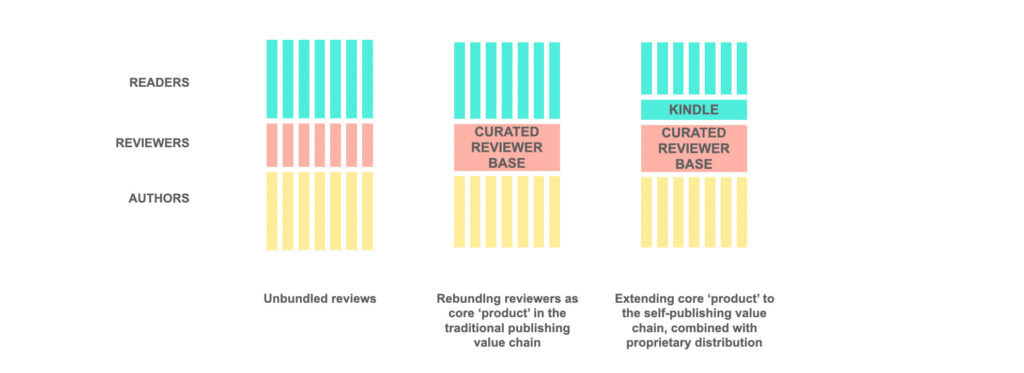

Traditionally, the large publishing houses bundled

(1) the ability to publish and distribute books, and

(2) through their PR arm, the ability to generate book reviews with media houses.

Even before the rise of the web, but particularly after it, book reviews started getting unbundled as peer-to-peer recommendations via email lists, and subsequently via blogs and social media.

Book reviewers were scattered across the web. Amazon – by establishing itself as the single place online to buy books – attracted a community of book reviewers.

Amazon curated this community of book reviewers leveraging supply of traditional published books from the large publishing houses. Leveraging this growing community of book reviewers, Amazon established itself as the point of rebundling of book reviews.

Once it had created this new locus of rebundling of book reviews in the value chain of traditionally published books, it then moved this ‘product’ into a new value chain – the value chain of self-published ebooks.

This transition is crucial. Amazon needed to play in the traditional publishing value chain to attract a curated community of reviewers which it then transferred to the self-publishing value chain. By combining the ‘curated community of reviewers’ with its proprietary distribution mechanism, Amazon established a chokehold over the self-publishing value chain.

Readers looking for new indie writing look to Amazon and its curated base of reviewers for guidance. For authors, it is far more effective to rack up reviews on Amazon than to work with hundreds of unbundled blogs and influencers.

The core ‘product’ establishes Amazon firmly at the centre of the self-publishing value chain.

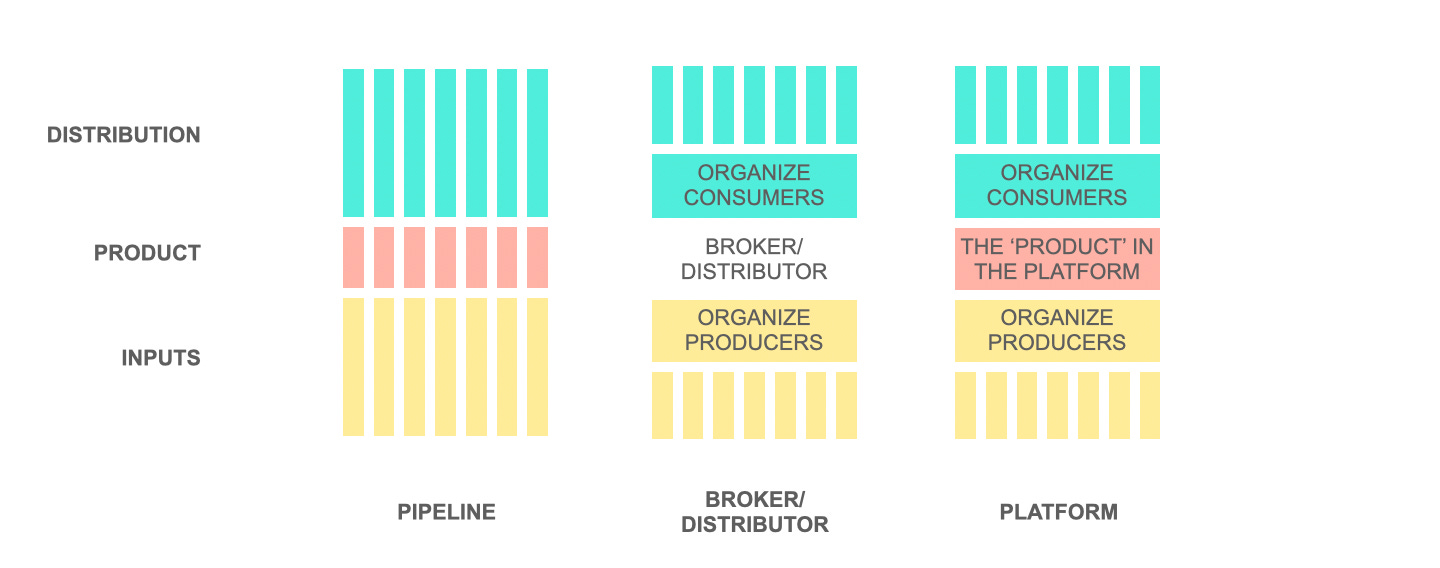

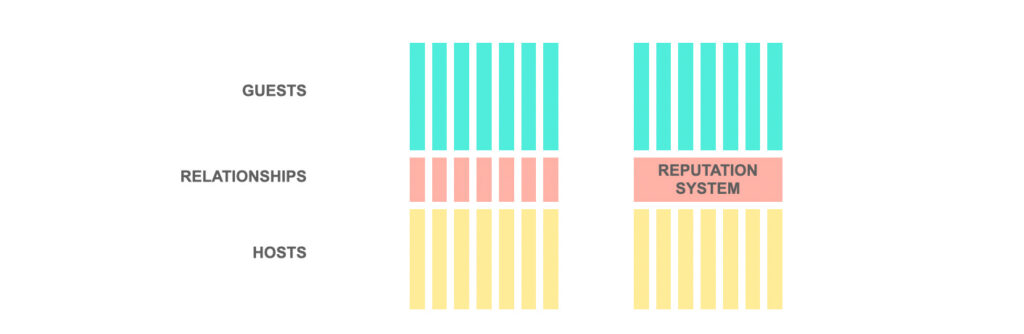

The ‘product’ as new value created by the platform

The best way to understand the product is to look at Spotify’s playlist. Arguably, the user’s need of ‘help me find a song to listen to’ is already solved by Spotify’s search function.

The playlist does something else. It helps Spotify create a new dynamic for music discovery and gives it the right to sit at the center of the music value chain having created new value.

Amazon’s book reviewers play a similar role. A search box is sufficient to help consumers fulfil their need and find books. But the platform creates a ‘product’ in delivering the ability to help unknown authors get rediscovered. That is a unique ‘product’ that is not available elsewhere and is not created through mere aggregation of inventory.

This is the key idea of finding the ‘product’ in your platform.

The product in food delivery platforms

Let’s look at food delivery platforms. What’s the ‘product’ here?

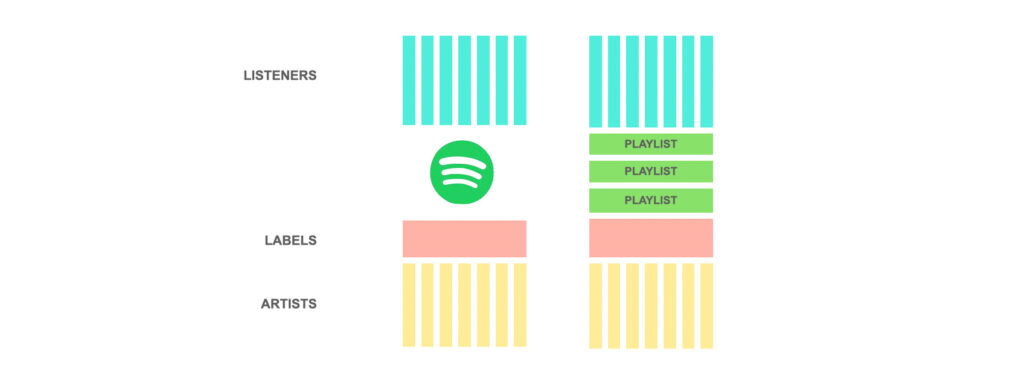

Having just looked at Airbnb and swayed by the ‘sharing economy’ catch-all phrase, you might be tempted to say it’s the driver and/or restaurant reputation system.

But you’re not really engaging in market transactions based on driver reputation and restaurant reputations, while somewhat important, do not determine the key vector of consumer experience in food delivery.

To identify the core ‘product’ in food delivery, let’s turn on the unbundling-rebundling lens again.

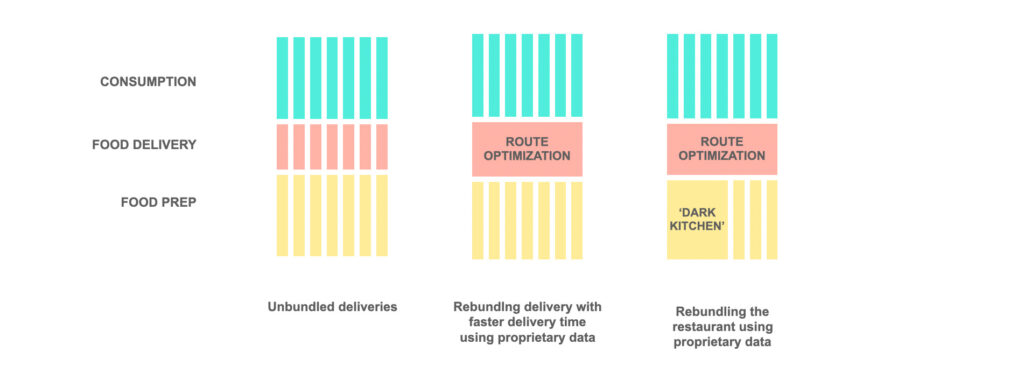

Restaurants that would manage their own food delivery would bundle food preparation and food delivery.

Food delivery platforms unbundle food prep from food delivery and rebundle food delivery using a near-captive base of delivery agents.

In doing this, these platforms gain a unique advantage over individual restaurants that managed their food delivery. They set up a market-wide data value chain where they gather demand data across the market and transform it into their core product: route optimization and delivery stacking algorithms.

Route optimization and delivery stacking, particularly in high-density cities in Asia and LatAm, enables food delivery platforms to differentiate on faster deliveries and gain a right to sit in the middle.

Food delivery platforms which decide to backward integrate into creating ‘dark kitchens’ create another important product: the standardized minimal menu of the dark kitchen. Demand data captured at market-wide scale informs these platforms of (1) what’s popular, (2) where it’s ordered from, (3) order patterns. These three data types help determine (1) location of ‘dark kitchens’ to minimize delivery times, (2) menu, and (3) estimates for ingredient sourcing and food production.

There’s an important nuance here. The product of the ‘dark kitchen’ is the food that’s created but the ‘product’ of the food delivery platform is the standardized minimal menu (what to produce) and the production schedule (when to produce), both of which are built off the market-wide data gathered by the platform.

Why most Banking-as-a-service platforms fail

Let’s look at a counter example.

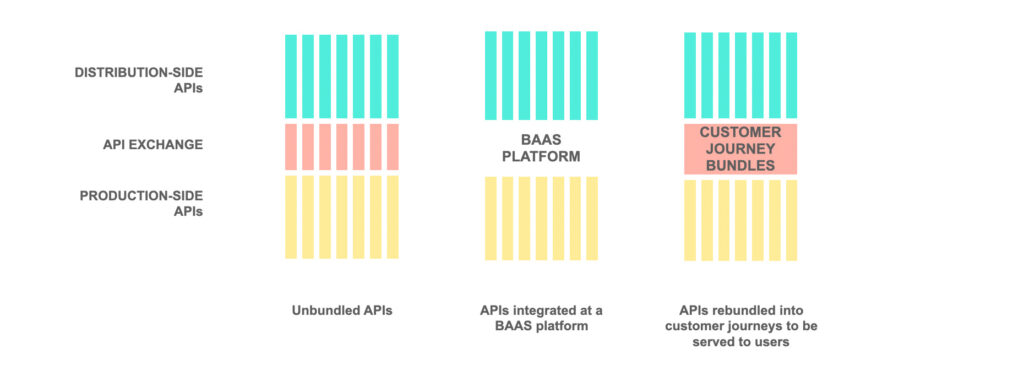

As firms increasingly open up APIs, business capabilities are being unbundled from organizations and are opened out to be rebundled externally into new products.

Take the financial services landscape as an example. As I point out in The financial services value stack:

The ability to modularize and provision financial services as APIs enables unbundling and rebundling in the financial services industry.

The API exchange layer (typically referred to as Banking-as-a-service platforms) manages interactions across the financial services stack. On one hand, this layer aggregates product provisioning APIs across the financial services production ecosystem. On the other hand, it integrates across websites, apps, and other digital services in the consumption ecosystem, providing them access to these APIs.

With every bank provisioning its product as APIs, players at the API exchange layer manage the aggregation and provisioning of these APIs across multiple banks.

This sounds simple enough. Aggregate production side APIs (inputs) on one side and integrate with consumption-side APIs (distribution) on the other, and create a one-stop integration layer.

Yet, most Banking-as-a-service (BAAS) platforms fail.

Neither the inputs nor the distribution are proprietary. Any substitute integration layer can also aggregate the same APIs.

The BAAS platforms that eventually win are the ones that are able to create ‘products’ at the point of rebundling. These ‘products’ are carefully crafted consumer journeys, typically created by:

- taking production-side APIs as input,

- wrapping them in core banking capabilities to make the APIs consumable by third-party non-banking entities, and

- rebundling them into a consumption-side customer journey.

BAAS platforms win when they develop deep customer insight into consumption-side journeys at their partners (e.g. buyer journey at an e-commerce store) and carefully curate the most relevant production-side APIs into that bundle.

BAAS platforms that do not create these ‘products’ fail.

The ‘product’, again, is created at the point of rebundling and give the platform the right to site in the value chain beyond being a market-wide integrator and distributor.

The not-so-obvious ‘product’ in your platform

You would have figures by now that to really get to the ‘product’ in your platform you need to reason with first principles, not with analogy.

As an example, Amazon Kindle Publishing, Airbnb, and Meituan/Grab/Zomato – all use reputation systems. Yet, the ‘product’ in their platforms isn’t uniformly the reputation system.

To get to the ‘product’ in your platform, try to identify the key vector of differentiation. For the three platforms above, this translates to:

- Airbnb: Assure me of a safe stay

- Amazon: Help me find a good book by an unknown author OR Help me get discovered as an unknown author

- Meituan: Help me get my food as soon as possible.

Note that this isn’t just the overall consumer problem. E.g. there’s a difference between ‘help me find what I’m looking for’ and ‘help me find a good book by an unknown author’. The first can be solved through aggregation alone, the second needs curation and rebundling.

Back to the three scenarios above… All three have reputation systems, yet reputation is not a key performance vector for Meituan. Delivery times – and, hence, route optimization and delivery stacking – matter more.

Between Amazon and Airbnb, the reputation problems are fundamentally different. The risk of a bad transaction is much higher on Airbnb (host physically harms you) than on Amazon (you read a crappy book). Reputation is, hence, the key performance vector in centralizing trust and delivering a safe market.

On the other hand, the reviewer base on Amazon plays a crucial role. First, unlike TikTok videos and Tinder swipes, where you can provide feedback on content instantly, reviewing books requires significant investment in reading the book. Gathering the right reviewers together who are keen to sample new books is far more important than just getting to scale with a rating system.

As the examples demonstrate, the ‘product’ in your platform will be determined by the key performance vector at the point of rebundling.

Two very similar platforms may have fundamentally different core ‘products’ based on the nature of their value chains and the specific role the platform performs within it.

Finding the product – why it matters

This post isn’t meant as a prescription, it’s meant to provoke debate.

Over the past decade, I’ve advised a very wide range of platform initiatives.

And I repeatedly see one issue emerge.

Business leaders are more focused on debating openness and finding new user bases and third parties to connect in to check the “Are-we-a-platform” checkboxes, than they are on clearly articulating why a platform is needed in the first place.

In essence, they’re more obsessed with finding the platform in their product than they are in determining whether there really is a product in the platform they are trying to build.

What’s the unique value created by the platform beyond merely bringing together demand and supply?

This is where it helps to take off the fancy platform thinking buzzwords and go back to the first principles of looking at your platform business as you would look at any business i.e. look for the ‘product’ in your platform business.

Don’t get me wrong – I love platform thinking – I literally wrote the book on this topic and have built more than a decade of work advising businesses and regulators on this topic.

But every so often, it’s important to come back to look not at what’s changing but what remains the same.

The central idea of a product in a value chain doesn’t go away with a change in business model. It’s a lot less clear what the core product is in a platform business model, but that’s precisely why clarifying it is all the more important.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this piece. If you’d like to kick these ideas around some more, feel free to leave a comment below.

State of the Platform Revolution

The State of the Platform Revolution report covers the key themes in the platform economy in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This annual report, based on Sangeet’s international best-selling book Platform Revolution, highlights the key themes shaping the future of value creation and power structures in the platform economy.

Themes covered in this report have been presented at multiple Fortune 500 board meetings, C-level conclaves, international summits, and policy roundtables.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter