Strategy

Platform ecosystems: Why they matter, the good and the bad – A deep-dive

Platform ecosystems have been one of the most important topics in business strategy since the early 2000s, as social and economic activity began to increasingly be intermediated by platforms. However, the terms platform and ecosystem are often used interchangeably and conflated.

This article explains:

- The difference between platforms and ecosystems

- Types of platform ecosystems

- The difference between ecosystems and traditional industries

- Factors that pitch a platform against its ecosystem

PLATFORM VS ECOSYSTEM

An ecosystem is a system of interacting actors who interact and coordinate towards a value creating outcome.

A platform, on the other hand, is an organizing mechanism that organized these interactions to achieve the above value creation outcome.

Together, they constitute the platform ecosystem.

Ecosystems can exist without platforms. For example, contracts and standards are alternate coordination mechanisms that may be used to manage ecosystems. Before the rise of platforms, most business ecosystems were coordinated through contracts.

It is important to make a distinction between production and consumption ecosystems.

PLATFORM ECOSYSTEMS: PRODUCTION VS CONSUMPTION ECOSYSTEMS

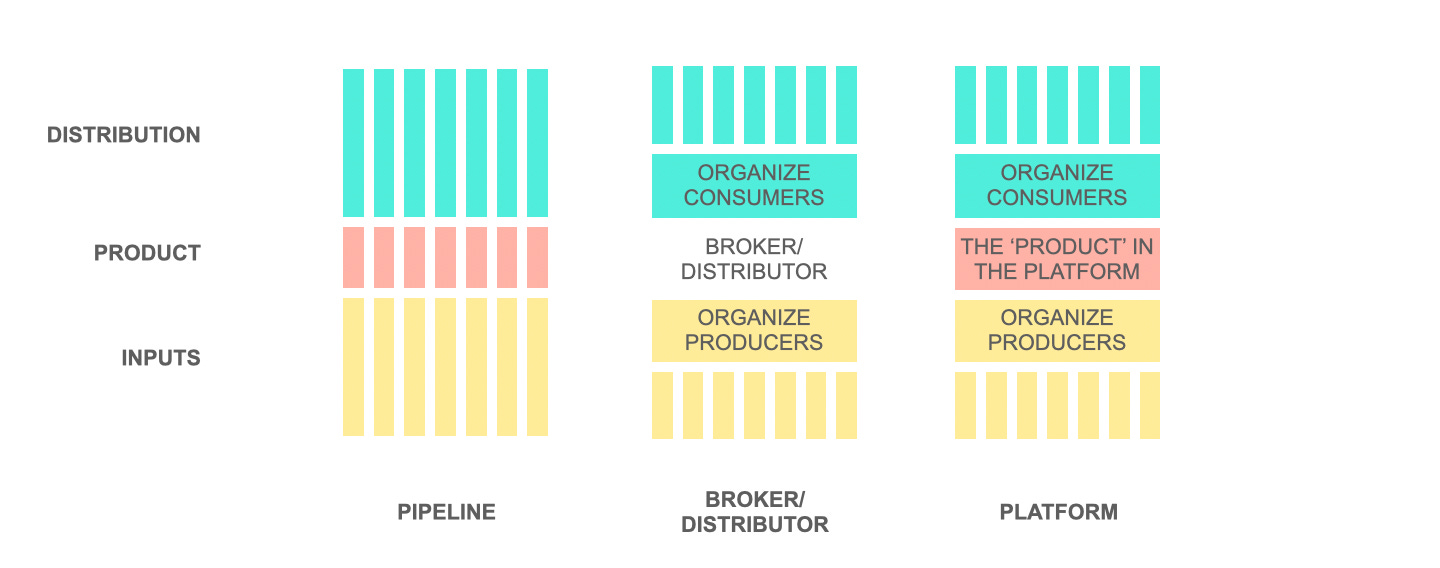

In the platform economy, the distribution of products and services is getting decoupled from the manufacturing of these services. Across the value chain, we see the emergence of distinct production and consumption ecosystems.

The production ecosystem comprises activities further up the value chain. These activities are organized around a core production process. The consumption ecosystem comprises activities further down the value chain. These activities are organized around jobs-to-be-done for the consumer.

Production ecosystems rely on mechanisms to coordinate components across firms towards a common production output, still centered around a customer value proposition. For instance, in the financial services industry, a mechanism to organize and standardize fraud detection across multiple financial institutions would create production efficiencies as each individual bank would benefit from the collective knowledge. Consumption ecosystems rely on mechanisms to reduce search costs for consumers by providing them one-stop aggregation and access across multiple providers. For instance, a recommendation system that recommends the most appropriate mortgage to a user, based on data from their home buying journey, reduces search costs that the user would have had to incur in comparing across multiple complex products and being evaluated by multiple financial institutions.

PLATFORM ECOSYSTEMS VS INDUSTRIES

Platform ecosystems are not built around products but around customer value propositions. Consider the financial services industry, for instance. The industry boundaries are structured around traditional financial products. However, these industry boundaries become less relevant in a world of ecosystems. A bank, for instance, may have to coordinate with players across industries – housing, automotive, local commerce, and others – to shape integrated customer value propositions.

Such partnerships would traditionally have been managed bilaterally, with limited ability to scale. However, in the platform economy, platform business models enable the reorganization of activity in business ecosystems and provide a scalable coordination mechanism to manage and coordinate ecosystem activity. In doing so, a platform often occupies a central position in its ecosystem, with partner firms being increasingly dependent on the platform to organize activity in the ecosystem.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST IN A PLATFORM ECOSYSTEM

As platforms scale, they may often adopt policies that put them in conflict with their ecosystem.

Below, we note some key case studies that lay out this challenge.

COMPETITION IN CROSS-INDUSTRY PLATFORM ECOSYSTEMS

When a platform owner also acts as a producer on its own platform, there’s a conflict of interest in the platform ecosystem.

This gets especially complex when the platform player has interests across industries. Consider Apple. In the music industry, Apple competes with Spotify. But as an App Store owner, Apple acts as a channel for Spotify. This allows Apple to attack Spotify through its channel ownership, towards the advantage of its music business.

This article presents an interesting set of issues between Apple and Spotify.

Conflict of interest: Platform-producer competition and the Apple Tax on Spotify

Remember handset manufacturers boycotting Symbian as Nokia gained greater control of the platform? Apple is far from a neutral platform in its relationship with Spotify, given the importance of music as a category for Apple. It leverages its distribution control points to levy taxes and restrictions on Spotify, to Apple Music’s advantage.

Money quote: “Apple takes a 30-percent cut on every Spotify subscription signed up via the App Store during the first year, and then 15 percent each year thereafter. “If we pay this tax, it would force us to artificially inflate the price of our Premium membership well above the price of Apple Music,” said Ek in a March blog post. Conversely, not paying the tax results in “a series of technical and experience-limiting restrictions on Spotify,” complains Ek, such as limiting communications with Spotify customers. Spotify’s complaint says that Apple unfairly targets music subscriptions with the tax but not apps like Uber or Deliveroo, for example.”

This price discrimination of sorts isn’t aimed merely at revenue maximization. It serves to choke competition by attacking their margins on Apple’s controlled channel.

THE CHALLENGE OF VERTICAL INTEGRATION IN PLATFORM ECOSYSTEMS

Another set of issues emerge when platforms vertically integrate and gain control of certain parts of the value network.

The Sonos vs Google lawsuit is a classic example of platform ecosystem conflicts that emerge when platform firms vertically integrate into non-platform positions in the ecosystem.

Platform and non-platform positions: Understanding Google vs. Sonos

Google plays at the platform layer with Google Assistant, as well as the device layer with Google Home. This allows Google to use its interface ownership with Assistant to engage in anticompetitive moves at other layers.

(The final straw) was Google using its Assistant voice command platform as a cudgel. Voice commands have become a standard feature on speakers, and Google Assistant is one of the most ubiquitous. While the company offers a free software development kit, it’s restricted to non-commercial use. That gives Google a lot of power over hardware makers, and Google may have used it to retaliate against Sonos. One anecdote suggests Google set stricter terms for using Assistant, for example, after receiving complaints about the patents.

Google also uses its control position with Assistant to discourage multihoming in its ecosystem.

Sonos wanted to roll out simultaneous support for Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa — an extra feature that would justify a higher price and set Sonos apart. But Google and Amazon reportedly forced Sonos to drop the plan. (Amazon denies that it did so.) Sonos executives claim that Google maintains a standing ban on Assistant working alongside any competing product from Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, or Baidu.

Google Assistant is an important control layer in the smart home ecosystem. A platform vertically integrating into another position in the ecosystem, in a way that limits fair competition, is one of the few instances where I believe the idea of breaking up big tech is justified.

Producers looking to join a platform need to carefully evaluate platform positions and identify potential conflicts of interest that may come up because of the platform’s information advantage.

Feel Free to Share

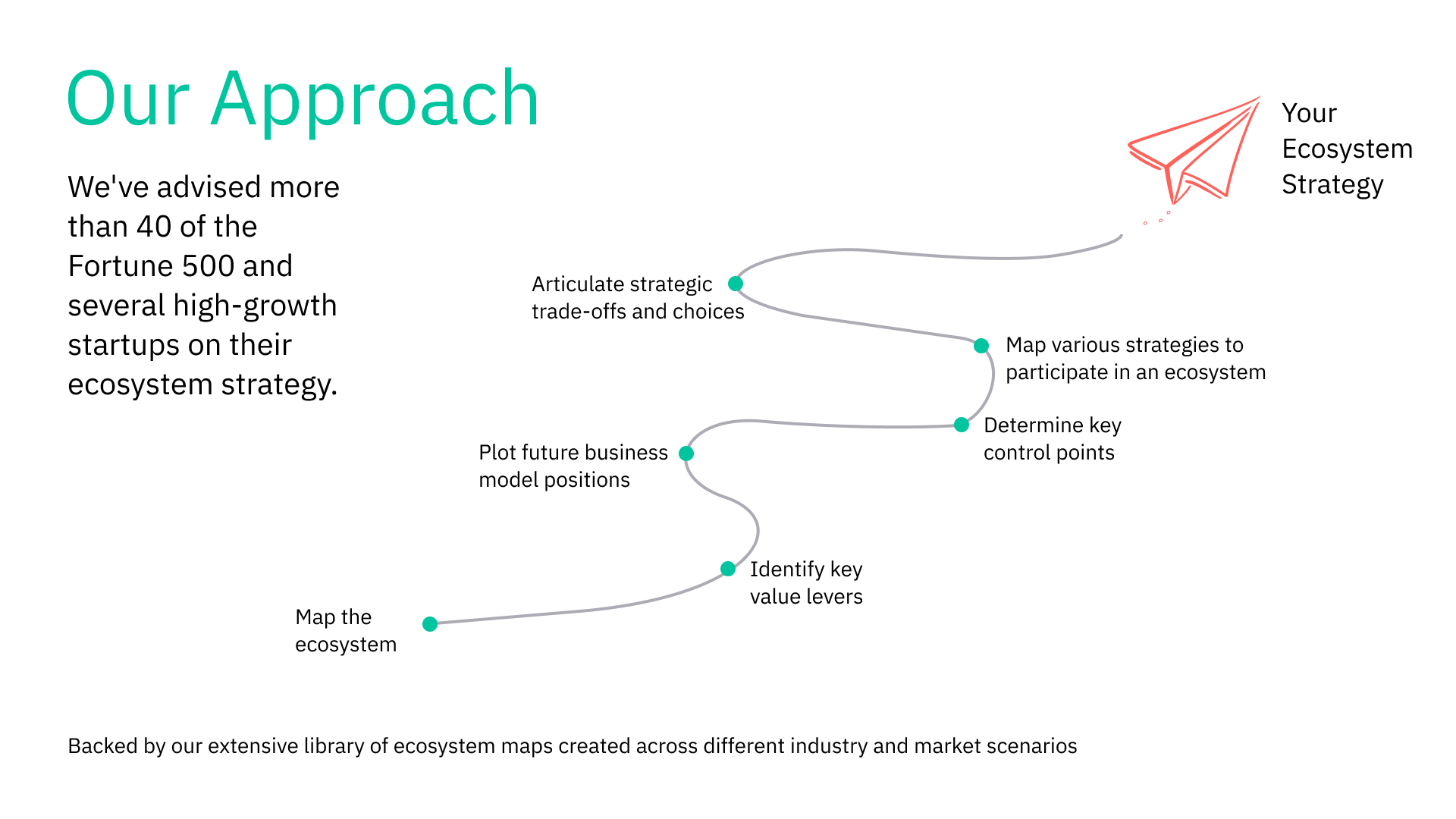

Map your

digital ecosystem strategy

- Leverage our extensive library of ecosystem maps created across different industries

- Determine potential value pools and business models in your industry

- Design and strategize for platform business models within the defined industry ecosystem

- Identify ecosystem control points to gain competitive advantage

ANTI-COMPETITIVE MOVES IN PLATFORM ECOSYSTEMS

Another way platforms dominate over smaller firms in the platform ecosystem is through predatory contracting.

I’ve written about this in detail before in this article.

As platforms gain dominance, they often demand “preferred customer” clauses from their ecosystem partners.

First, when a platform starts to dominate the market, it can raise the fees it charges sellers. A dominant platform can do so without the fear of destroying the network effect. An up-and-coming platform is less likely to do so. Sellers aren’t left with much choice in such cases.

And the classic bait-and-switch move depending on which side of the network effect you are on.

Platforms often bait and switch in this manner. They attract the ecosystem with lower fees and deeper incentives when network effects are low. As the ecosystem builds around the platform, network effects increase and the platform starts moving towards winner-take-all. The dominant platform can work against the interests of its partners without fear of destroying the network effect.

Predatory contracting also eventually kills competition.

Consider a new platform that launches and wants to attract partners by offering them better economic terms than the dominant platform. These could involve lower selling fees or other subsidies like free promotions. These terms, in turn, may encourage sellers to reduce prices on the new platform. In such a case, the dominant platform can once again leverage the preferred customer clause and force sellers to offer the same lower prices. However, it is under no obligation to give sellers the better economics they enjoy on the new platform. As a result, sellers are hesitant to join the new platform because any price reduction on it, when mirrored on the dominant platform, would translate to lower margins for them. Thus sellers go on with the dominant platform and the new platform never takes off.

THE ‘GOD VIEW’ IN PLATFORM ECOSYSTEMS

This term got popularised by Uber but every platform has an all-knowing view on interactions in the platform ecosystem that it facilitates.

A ‘God View’ clearly comes laced with privacy concerns. But having an all-knowing view of platform ecosystem activity also raises concerns around the platform engaging in anti-competitive moves using this knowledge. I’m, of course, using the term much more broadly than just referring to a specific Uber-style tool.

A ‘God View’ gives the platform an unfair advantage over other producers in the platform ecosystem. We’ve seen this play out in the past (Nokia vs. other handset manufacturers on Symbian) and continue to see it on several platforms today (Amazon vs. merchants on the Amazon Marketplace).

Some platforms may use the ‘God View’ to work against producers. If the producers are small and fragmented, they have little choice, but if they are large and well organized, they can abandon the platform and collude off it with a (relatively) independent player.

HOW THE BIG4 DOMINATE THEIR PLATFORM ECOSYSTEM

How the Big 4 Tech firms use their ‘God View’ to kill competition

This article offers a quick overview of anti-competitive moves by the big 4 tech firms. It fundamentally comes down to the ‘God View’, originally a term used by Uber, which can be extended to imply the all-knowing visibility and insight that a platform has over the market.

FACEBOOK’S ANTI-COMPETITIVE MOVES IN ITS ECOSYSTEM

Facebook takes it a step further when building a ‘God View’. Facebook’s app Onavo directly informed its acquisition of Whatsapp. A few interesting snippets from the article linked above:

“Among the apps Facebook distributed was a VPN called Onavo Protect. The VPN billed itself to users as a way to keep data private by encrypting it—basically, what a VPN is for. However, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2017 that when users opened an app or website, Onavo was redirecting the traffic through Facebook servers, which logged the data. That data directly informed Facebook’s largest-ever acquisition, the WSJ reported: its $19 billion purchase of messaging platform WhatsApp in 2014. “Onavo showed [WhatsApp] was installed on 99% of all Android phones in Spain—showing WhatsApp was changing how an entire country communicated,” sources told the WSJ.”

And here’s what happens if you reject Facebook’s acquisition efforts:

“Instagram influencers with verified accounts were reportedly warned that mentioning Snap could cost them their coveted blue check mark. Snap executives also suspected Facebook was suppressing content that originated on Snap from trending on Instagram.”

APPLE’S ANTI-COMPETITIVE MOVES IN ITS ECOSYSTEM

“Apple has a history of using App Store sales data as something of a free focus group for its own development team… uses App Store sales and download data to see which third-party apps gain the most popularity with iPhone users. Apple can then develop a similar app or feature set in-house and distribute it as part of iOS, or the company can promote it more heavily as a native Apple program.”

Apple uses its platform dominance with App Store search to also work against competing producers.

On Spotify again:

” In September 2013, Spotify was the first result returned by searches for “music.” By June 2016, Apple Music was the first result, and Spotify was down to fourth place—arguably, something that could have happened naturally. By February 2018, though, Apple first-party apps were suddenly the first six results for “music,” with Spotify coming in at number eight. And by December 2018, Apple native apps came back as the first eight results in the same search, even though some were completely unrelated to music—and Spotify, one of the world’s most popular music streaming services, was all the way down to 23.”

Google and Amazon have similarly used their control over search and recommendation to participate profitably in interesting niches and demote competitors.

The common thread across all these moves is the information advantage that platforms possess on account of convening the market. Many of today’s anti-competitive moves come up because of this information advantage.

Producers looking to join a platform need to carefully evaluate platform positions and identify potential conflicts of interest that may come up because of the platform’s information advantage.

DESIGN YOUR PLATFORM ECOSYSTEM

The ecosystem stack mapped out in our Ecosystem Innovation Playbook lays out a central framework for developing strategy in modular ecosystems. The financial services industry, in particular, has been transformed with the shift to modular ecosystems.

To strategize future positions in these ecosystems, firms must map out their overall ecosystem value stack and identify key positions and business models that grant them competitive advantage.

To strategize across the stack, firms must follow a four-step approach:

- Determine current positions across the value stack where they continue to play and current positions they abandon because of impending commoditization.

- Select future positions that provide competitive advantage which they wish to migrate to, and map out build-partner-buy options to aid that migration.

- With this portfolio of future positions across the stack, identify factors that reinforce value and defensibility across these future positions by developing business models that integrate multiple positions.

- Develop a reliable, self-learning mechanism to continuously monitor competitor moves, particularly moves by non- traditional competitors moving in adjacent stack positions.

Need help with your ecosystem strategy?

State of the Platform Revolution

The State of the Platform Revolution report covers the key themes in the platform economy in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This annual report, based on Sangeet’s international best-selling book Platform Revolution, highlights the key themes shaping the future of value creation and power structures in the platform economy.

Themes covered in this report have been presented at multiple Fortune 500 board meetings, C-level conclaves, international summits, and policy roundtables.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter