Concepts

Beyond the Softbank farce: Three key ideas about platform valuations

A lot has been said about SoftBank’s frothy valuations, ranging from WeWork’s collapse to Uber’s lacklustre public performance, and most recently, Oyo’s challenges (which are getting worse post-Coronavirus).

The problem with valuation discussions is that they get polarized rapidly, and end up missing most of the nuance.

This issue focuses on three key factors that impact valuations:

- Unit economics: Getting the basics right gets difficult when you’re surrounded by froth

- Valuation of network effects: When is a network effect defensible and when is it not?

- Inventory risk: In a world where everyone claims to be a platform, the level of inventory risk you carry makes all the difference.

Let’s jump into these three ideas.

1. Unit Economics 101

Do the unit economics make sense?

You need to solve a customer problem to get to product-market fit. But you need to make the unit economics work in order to solve it at scale.

This is where some startups get it wrong. They remain too focused on solving for product-market fit and don’t think enough through the unit economics of the model.

Case study #1: BlueApron

BlueApron, an ingredient-and-recipe meal-kit service, IPO’d in June 2019 and has been struggling with unit economics ever since.

TLDR: Unit economics 101: Keep your CAC lower than your LTV.

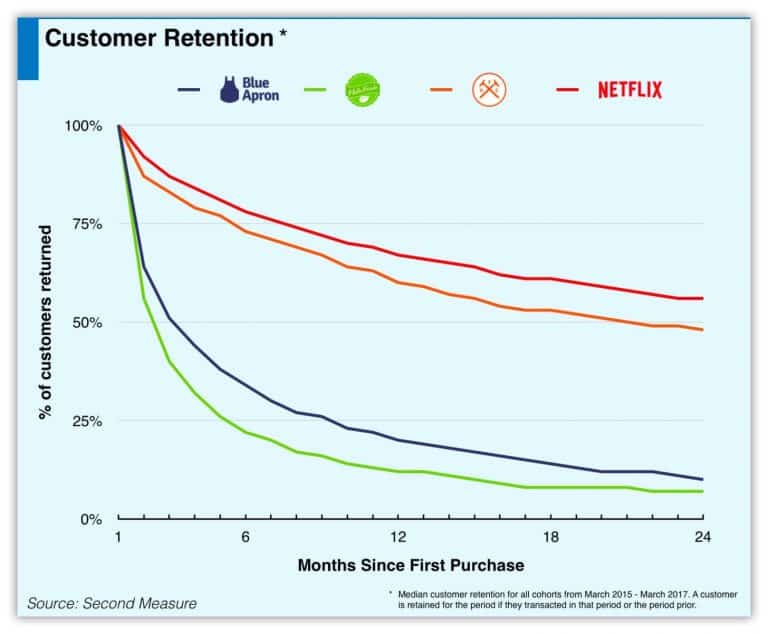

Adam’s Twitter thread comes down to one simple graph by Second Measure:

BlueApron has a roughly 30% retention at the 6 month mark and a roughly 20% retention at the 1 year mark.

To manage CAC vs LTV, you need to track:

1) churn and

2) number of transactions needed to recover CAC.

You can either:

1) Reduce churn (by increasing engagement) or

2) Reduce the number of transactions to recover CAC (by increasing average order size).

Case study #2: HonestBee

HonestBee, an on-demand grocery delivery startup in Singapore learnt the hard way that value propositions scale only if unit economics work.

This TechCrunch article is a good introduction.

Note the founder Chiang says

“Honestbee’s advantage is that it appeals to customers who want certain products from their favourite stores that RedMart might not carry, as well as lower minimum orders for delivery fees.”

All this sounds great from the perspective of delighting customers and finding product-market fit. But do the economics make sense? The economics of picking and packing from a fully automated fulfilment center are much more attractive than picking and packing from diverse, non-standardized merchants in the ecosystem.

As a result, on-demand platforms are increasingly moving towards setting up their own fulfilment centers.

Grocery delivery is a unit economics game.

RedMart – a competitor to HonestBee in the online grocery space – got this right and picked on the issue around unit economics fairly early on

Money quote: “The on-demand marketplace works for certain product categories but I don’t think it scales for groceries. In groceries, you have many more items per order than other ecommerce. So, the efficiency of picking and packing those orders becomes really important at scale.”

“Picking and packing from a physical store can never be as efficient as a fully automated fulfillment center. It’ll always cost more per pick. It’s good for lowering delivery time and for convenience. But once you have to scale up, it’s not as efficient because physical retail space is more expensive and has less throughput.”

Case study #3: UberEats

Revenue is split three ways in food delivery vs. just two way as in ridesharing

Money quote: “Uber is currently losing $3.36 on every order. They expect that loss to shrink to $0.46 per order by 2024, but didn’t say anything about when the food-delivery business might turn a profit.”

“Food delivery is more complicated than ride-hailing because there are more parties involved in the transaction. In the typical ride, Uber collects a fare from the rider, pays out a portion of it to the driver, and pockets the rest. In the typical food-delivery transaction, Uber makes money by charging fees to the customer and taking a cut of the bill from the restaurant, and then pays the delivery person. That can make margins in food delivery particularly thin, because the money is split between more people.”

Focusing on this one metric is essential to determine whether there's a business that's scaling on fundamentals here.

Feel Free to Share

Download

Download Our Insights Pack!

- Get more insights into how companies apply platform strategies

- Get early access to implementation criteria

- Get the latest on macro trends and practical frameworks

2. Defensibility of network effects

Are network effects creating a defensible moat?

Network effects are great but they are not all made equal. I’ve talked about this before in my book Platform Scale.

Case study #4: Uber

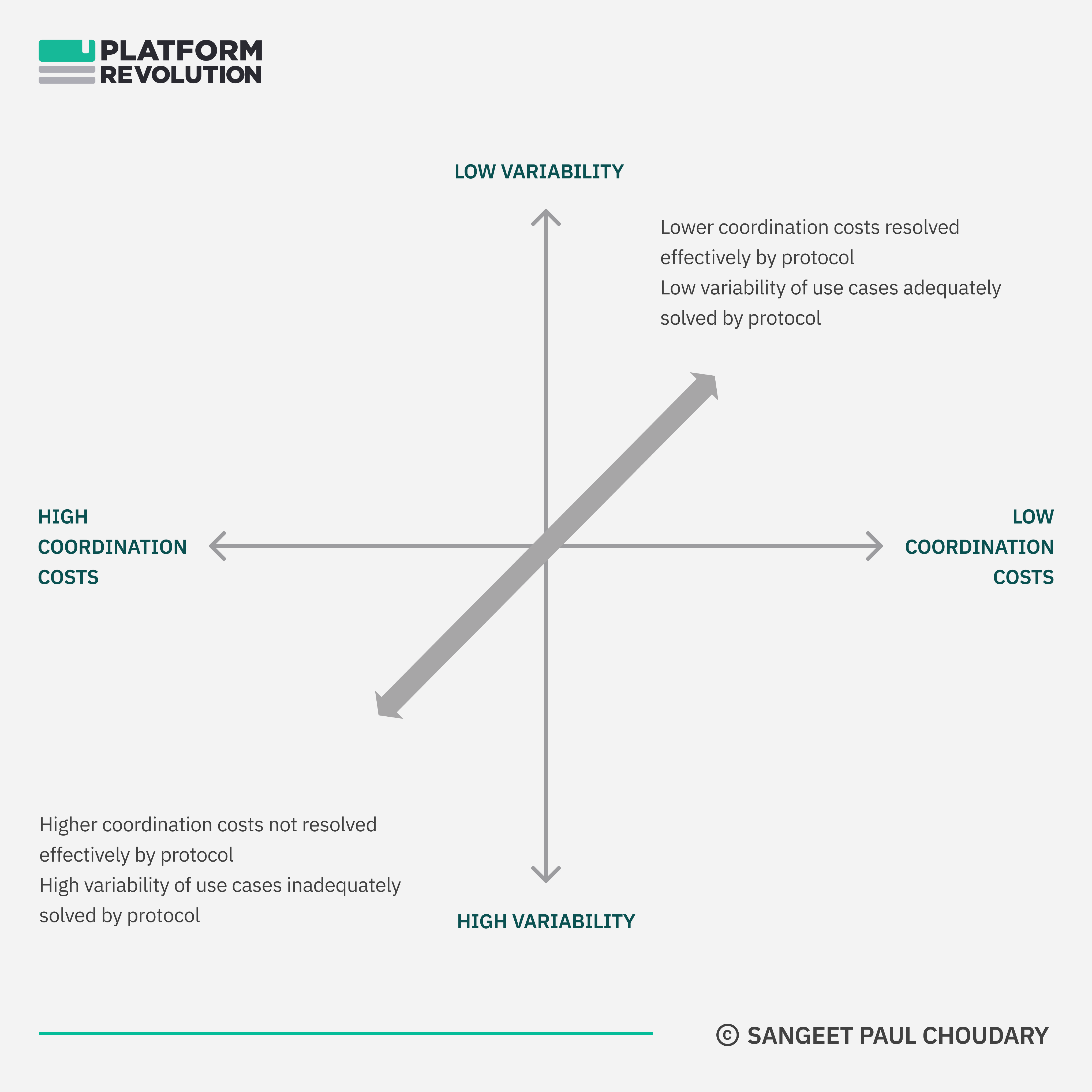

Uber’s network effects come with low multihoming costs. For network effects to be truly defensible, you need high multihoming costs, which effectively coalesces the market in your direction.

Money quote: “When multihoming costs are low, producers and consumers will connect to many platforms. With multiple platforms sharing the same producers and consumers, it is difficult for a business to build defensible networks. Thus, it is difficult for a clear winner to emerge in the market. With many platforms operating and defensibility low, interaction failure becomes a key factor in determining long-term winners.”

This is also why Uber competitors like Grab and Gojek have been trying to create a larger ecosystem and have been moving away from transportation as their core to payments as their core. This ‘super app’ strategy can combat the issue with low multihoming costs as it gives the player control of the wallet across a larger ecosystem. In this play, you are no longer just a transportation play, you transform to a payments play.

With this shift to super apps, Grab claims that “ridehailing represents less than a quarter of its overall gross merchandise value.”

Meanwhile, in a bid to create a defensible model, Uber is now shifting to the super-app model itself.

Key idea: Not all network effects are created equal. Defensible network effects require high multihoming costs.

3. Inventory risk

Is the company playing an arbitrage game in a bull market?

One of the challenges with valuing companies like WeWork in a bull market is that you can potentially show growth AND profitability (not that WeWork did) by constantly playing an arbitrage game where you buy low and sell high. This works in a market where prices are rising but comes with the risk of holding inventory. So the business model starts to unravel when the market faces a downturn.

Case study #5: WeWork

First up, WeWork has always been a real estate leasing firm hiding behind a tech (worse still, platform) narrative. As a real estate firm, WeWork takes on inventory risk, especially with the long term contracts it’s been signing. Equally important, WeWork has an inverse scale effect in every city. The more premium inventory it takes on, the lower the availability of premium inventory, making the acquisition of the remaining inventory more expensive as landlords hike prices.

Case study #6: OpenDoor

Opendoor, also a unicorn, purchases homes from sellers, renovates them, and then flips them for a profit. It takes significant inventory risk, but in this case the inventory is easily quantifiable.

This brings us to…

This article breaks down succinctly how to think about metrics and risk with such a business model.

Opendoor’s inventory risk comes down to one single metric: “number of “prep days” between when Opendoor buys a home and subsequently lists it for sale.”

In fact, Opendoor seems to be doing much better than competitors on this particular metric.

Money quote: “OfferPad is holding homes longer than its competitor — over three times as long! In a world where time is money, this represents a significant business model and financial disadvantage for OfferPad. The longer it holds homes, the higher its holding costs.”

Focusing on this one metric is essential to determine whether there’s a business that’s scaling on fundamentals here.

But if the current coronavirus-induced changes lead us into a downturn, managing this one metric could be a challenge. In a downturn, decreasing prices impact not only margins but also lead to longer inventory holding times, and hence greater holding costs, thereby reducing margins further.

Key idea: When coming out of a bull market, watch out for inventory risk.

State of the Platform Revolution

The State of the Platform Revolution report covers the key themes in the platform economy in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This annual report, based on Sangeet’s international best-selling book Platform Revolution, highlights the key themes shaping the future of value creation and power structures in the platform economy.

Themes covered in this report have been presented at multiple Fortune 500 board meetings, C-level conclaves, international summits, and policy roundtables.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter