Concepts

When social fails: How sampling costs kill social curation

Social Curation: Pitfalls and Perspectives

Social curation is a great way to scale any business relying on user-generated content. YouTube and Quora enable the community to create value through upvotes/downvotes and the ability to report abuse. Startups that rely on user-generated content often scale when they unlock social curation.

For all its benefits, social curation isn’t fool-proof. Curation may still leave a lot of noise in the system, and I’ve explored this in detail earlier while explaining Reverse Network Effects. However, this view looks at why curation works or doesn’t work from the point of view of the platform.

Through this article, I’d like to present an alternate view. Startups may fail because the individual users that make up the community refuse to curate. And this happens largely due to sampling costs.

Uh… Sampling what?

Sampling is a concept I borrow from the world of traditional retail. New product introductions at retail stores often start with sample packages being distributed/bundled for free. Unless users sample and experience value, they won’t buy.

This actually applies to every consumer decision. Sampling is a way for consumers to

a) Make a decision regarding quality: This decision helps not only with their own consumption experience but also helps them signal the decision to others.

b) Provide feedback to the producer: If inventory doesn’t move at retail stores despite sampling, you’ve got a problem on your hands.

Social Curation Systems and Sampling

On platforms, a social curation system works in pretty much the same way. It captures all the sampling decisions made by consumers. But it doesn’t stop there. Unlike retail sampling, social curation goes a step further and aggregates these inputs to create:

1) Social proof for new consumers to base their decisions on: Number of upvotes may help a user decide which answer to read first for a question on Quora.

2) Quality scores for ranking algorithms: Votes on a video determine where it shows up in search results on YouTube.

3) Feedback loop for the creator: Creators receive feedback for their creations, as in the case with 500px and Dribbble.

A social curation system is essentially the weighted sum of all sampling decisions.

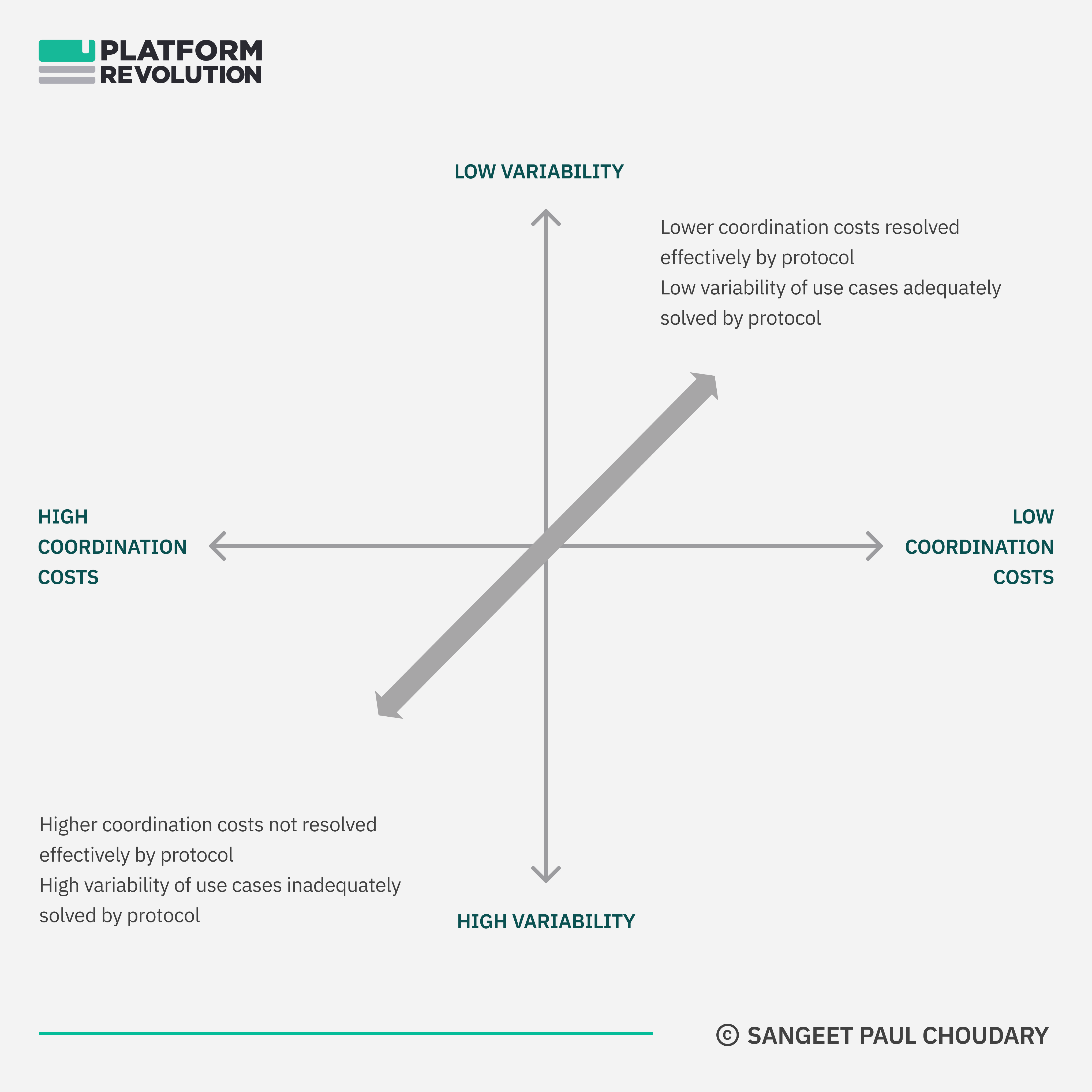

Why social curation systems fail: Sampling Costs

Every decision to sample has costs associated with it. Finding new artists to listen to by sampling a random assortment of artists is time-consuming. Rummaging through YouTube is equally time-consuming.

But this gets even more inefficient as the costs increase. Choosing a course to study by sampling twenty different courses can be a very inefficient exercise. This is why education cannot work on a YouTube-style curation model. When sampling costs are high, editorial discretion on what gets featured on the platform and what gets left out can be quite valuable. Voting systems won’t work on Udemy the way they work on YouTube.

There are scenarios where sampling costs can be so high as to discourage sampling. Healthcare, for example, has extremely high sampling costs. Going to the wrong doctor could cost you your life. In such cases, some form of expert or editorial discretion needs to add the first layer of input to a curation system.

The advantage of social is that at scale, it will likely be less biased than editorial judgment. The more expensive it is to sample some form of content or service, the more time it takes to achieve that scale where social works very well. And that’s why social tends to be more inefficient with higher sampling cost.

This boils down to the following:

- Look at the basic unit of content that is produced on your platform. On YouTube, this is a video. On Quora, this is an answer. On Udemy, this is a class.

- Determine the cost (in terms of time, money, risk etc.) that is required to evaluate that unit of content, on an average.

In general, I’ve observed the following across platforms:

The higher the sampling cost, the worse will a social curation system perform.

Photo Credits: steven w

To maintain a high signal-to-noise ratio in an online community, you need a community culture of quality.

Feel Free to Share

Download

Download Our Insights Pack!

- Get more insights into how companies apply platform strategies

- Get early access to implementation criteria

- Get the latest on macro trends and practical frameworks

Going beyond content… to services

Services marketplaces like Upwork, Fiverr, Airbnb, and TaskRabbit rely on social curation. In these instances, two factors are critical in determining the effectiveness of social curation:

1. The ability of the platform to retain the transaction

2. The service cycle

When a platform can actually mediate the exchange of services, it is likely to be more successful in enabling users to curate. e.g. UpWork and Clarity enable the exchange of services on-platform whereas Airbnb and TaskRabbit require the exchange of services to be conducted off-platform.

When the actual exchange occurs on-platform, the consumer of services (and in some cases, even the producer) can be asked to rate the other party in-context.

In cases where the exchange occurs off-platform, the service cycle serves as a proxy for the sampling cost. The longer the service cycle, the more difficult it can be for the platform to get the consumer (or producer) back in and rate the other party. Platforms often rely on incentives to encourage curation in case of long cycles.

Sampling decisions with inherent bias

Costs are not the only problem with sampling decisions. Some sampling decisions may suffer from an inherent bias.

To understand this, let’s look back at a problem we’ve seen before in the world of internet startups. There was a slew of startups in the 90s that paid users in order to view ads. They didn’t have much problem getting traction among users, but the advertisers realized fairly soon that the model was self-defeating. Users who were interested in viewing ads for money, typically, were the ones who didn’t have enough money to spend on making any related purchases. There was no point in showing them any ads.

The same applies to sampling. If sampling costs are high, e.g. in terms of time, you may automatically attract only those who have surplus time but who may not necessarily be the ones with the best judgment.

Using bias deliberately to filter curators

The above scenario should be differentiated from curation systems which need to be biased to allow only certain types of users to curate. E.g. Agoda allows only users who have already booked and taped at hotels through them, to rank those particular hotels. This prevents users from entering false reviews, a problem that is often associated with TripAdvisor. However, this is a system that is deliberately designed for bias to restrict curation to certain types of users.

Sampling may be subjective and may require a culture to be set

Social curation doesn’t kickstart on its own. As with any system that organizes people towards a common end, some form of culture needs to be set to encourage certain behaviors and discourage others. This is especially important when sampling decisions are subjective. E.g. decisions to down vote answers on Quora are very subjective. To avoid rampant down-voting, or the lack of it when needed, users need to be made aware of the Do’s and Don’t’s of down-voting. Since users won’t read or subscribe to a set of rules, they need to be invited into a culture that encourages or discourages behaviors. At scale, culture provides feedback from a community rather than a set of enforced rules.

In general, community culture helps when sampling decisions are subjective and ambiguous.

Social may work only at scale, start manually

This is a problem with most social curation systems. And this is why most startups are better off starting with editorial curation and gradually opening out the curation systems to a wider community. Quora and Wikipedia scaled very well using this model. In its early days, Quora editors and administrators handled a lot of curation. As the community grew and took over the curation, the editors scaled down. Of course, in all such cases, building reputation systems to differentiate good curators from bad ones helps to scale curation while keeping noise at bay.

In some cases like education, editorial judgment may be important even at scale. With entertainment content, social may play a far larger role with editorial judgement weeding out the noise.

Systems that scale and leverage the community best, often start as manual systems.

Again, social is not one-size-fits-all

Upcoming startups often copy features from successful ones. The problem with copying features, though, is that one doesn’t always look at the underlying influencing factors which make those features work. I’ve talked to startups who wanted to put in a voting system just because it ‘seems to work for others’. Understanding sampling costs helps us figure that such systems are not a one-size-fits-all feature that can be applied across platforms.

In summary,

1) For the basic unit of content on your system, determine sampling costs

2) Start with editorial curation

3) Depending on sampling costs, scale gradually from editorial to social while maintaining editorial oversight.

4) If sampling costs are too high, break down part of the curation to social and keep the rest in-house

Tweetable Takeaways

User-generated content platforms and services marketplaces scale value through social curation. Tweet!

Startups may fail to execute on social curation because of high sampling costs. Tweet!

Startups that leverage the user community effectively often start things manually. Tweet!

To maintain a high signal-to-noise ratio in an online community, you need a community culture of quality. Tweet!

State of the Platform Revolution

The State of the Platform Revolution report covers the key themes in the platform economy in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This annual report, based on Sangeet’s international best-selling book Platform Revolution, highlights the key themes shaping the future of value creation and power structures in the platform economy.

Themes covered in this report have been presented at multiple Fortune 500 board meetings, C-level conclaves, international summits, and policy roundtables.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter